By Neenah Payne

By Neenah Payne

The Official Schedule of Events says the Santa Fe Market will celebrate its centennial from Wednesday, August 17 to Sunday August 21, 2022.

When I went to the Santa Fe Market, I got the awesome pottery below and some beautiful jewelry. There are so many events to attend including musical performances and dances.

See PDF with many additional products and images, as well as contact info.

Santa Fe Indian Market 2017

Sights & Sounds — 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market

Santa Fe Indian Market 2018

Santa Fe Indian Market – Native Report

Santa Fe Indian Market 2019

2019 Santa Fe Indian Market video report

Santa Fe Indian Market 2020

The Santa Fe Market 2020 was cancelled because of the COVID hysteria.

So, it went virtual. Santa Fe Indian Market Is Virtual! (video)

“While the in-person Santa Fe Indian Market was cancelled due to COVID-19, the event is moving ahead online through August 31, 2020. The annual market has a rich history in supporting Native arts. First launched in 1922, the annual market attracts more than 115,000 people each year. This year’s artists include a number of current and past NACF awardees.”

Virtual Santa Fe Indian Market 2021

“The Santa Fe Indian Market provides a vehicle of personal and cultural sustainability for Native artists. It is an opportunity for Native people to represent themselves to the world and build lasting relationships. SWAIA cultivates excellence and innovation across traditional and non-traditional art forms and develops programs and events that support, promote, and honor Native artists. Quality and authenticity are the hallmarks of the Santa Fe Indian Market. To ensure the quality of the artwork being sold by artists, SWAIA drafts and maintains standards to ensure that only original art is sold. In addition to the Saturday and Sunday market, there is a calendar of other events to enjoy.”

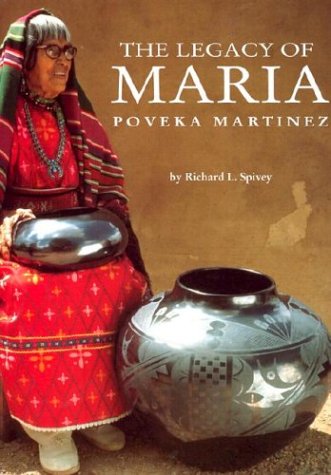

Maria Martinez: Black Pottery

When you talk about black pottery, you must start with Maria Martinez (1887–1980), the potter of San Ildefonso. The famous black pottery of New Mexico comes from San Ildefonso and Santa Clara, neighboring pueblo villages just north of Santa Fe. Starting in the early 20th century, Maria and Hopi potter Nampeyo, turned utilitarian ware into an art form.

Maria Poveka Martinez, born in 1887, married Julian Martinez in 1904. In 1907, after seeing prehistoric shards of pottery, they ventured into pottery. By 1919, they were making prize-winning polychrome pottery with superior designs and technique, but also began to experiment with black-on-black. Maria made the pots, polished and fired them, but never the designs. Julian painted the designs on the pottery until his death in 1943 when members of Maria’s family created the designs. Maria made many pots with just her famous polished black finish. Popovi Da was their legendary son.

Martha Appleleaf Fende, the daughter of famous San Ildefonso potter, Carmelita Dunlap, is one of the few San Ildefonso potters to maintain the classic style of the pueblo. Her mentor was her mother, Carmelita. She also received her early training from her aunts, Maria Martinez and Disideria Montoya.

“Many of Martinez’s family members were involved in producing pots, and she learned to make pottery in the traditional way—watching her aunt and grandmother work. By age thirteen, she was already celebrated within the tribe for her creative skills. She and her husband, Julian Martinez, revived an ancient local process for making the all-black pottery. Their blackware stood in marked contrast to the all-red or polychrome ware that had dominated the pueblo’s production for generations.

By the mid-1920s, Martinez’s blackware had become extremely popular outside the pueblo, thanks to a book published by the director of director of the Museum of New Mexico. Martinez was encouraged to sign her pots, which were beginning to be regarded as works of art rather than household or ritual vessels. Martinez was awarded two honorary doctorates, had her portrait made by the noted American sculptor Malvina Hoffman, and in 1978 was offered a major exhibition by the Smithsonian Institution’s Renwick Gallery.”

Read: The Legacy of Maria Poveka Martinez and The living tradition of Maria Martinez.

Amazon Descriptions

“Maria, the potter of San Ildefonso (1887–1981), is not only the most famous of Pueblo Indian potters but ranks among the best of international potters. Her work is collected and exhibited around the world, and more than any other artist, Maria Martinez brought “signatures” to Indian art. She and other members of her family revived a dying art form and kindled a renaissance in pottery for all the Pueblos.

She raised this regional art to one of international acclaim. This lavishly illustrated book draws from Spivey’s 1979 classic work. Featuring entirely new photography and 120 added pots as well as a significantly expanded text, this volume considers the entirety of this artist’s immense oeuvre and important works and developments in her collaboration with Julian, and after his death, with her daughter-in-law Santana, son Popovi Da, and grandson Tony Da, bringing the legacy of Maria into the bright future of Pueblo ceramics.”

“Maria Montoya Martinez (born 1887 in San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico—died July 20, 1980 in San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico) was a Native American artist who created internationally known pottery. Martinez (born Maria Antonia Montoya), her husband Julian, and other family members examined traditional Pueblo pottery styles and techniques to create pieces which reflect the Pueblo people’s legacy of fine artwork and crafts.

Traditional pottery making techniques were being lost, but Maria and her family experimented with different techniques and helped preserve the cultural art. She became a legend in her lifetime, and is internationally known for her magnificent burnished black pottery perfected by Maria and her husband. This book is the culmination of the author’s nearly 30-year association with Maria and her family. Profusely illustrated with black-and-white and color photographs. Pueblo Pottery; Indian Pottery; Native American Artists.”

History of Santa Fe Indian Market

“What began in 1922 as an adjunct to the annual Fiesta celebration has grown to become the world’s largest, most prestigious independent Native American arts market, and one of the biggest annual cultural events in the Southwest. Now, it is difficult to believe it ever fit inside one building.

In the early 1900s, Native American arts and crafts were sought after by travelers and traders for souvenirs and curios. They wanted something small enough to fit in their travel bags and suitcases. This level of collecting served to endanger the value and craftsmanship of Native art.

Well-known archeologist and anthropologist Edgar Lee Hewett, whose studies focused primarily around the Native cultures of the Southwest, was a prominent figure in support of the preservation and conservation of the cultures’ traditional art forms and prehistoric dwelling ruins. In 1909, he founded and directed the Museum of New Mexico. Museum curator and assistant director Kenneth Chapman worked closely with Hewett and saw the need for educating the public at large on the value of genuine indigenous Southwest arts, if appreciation for the genre was to be sustained.

Hewett, Chapman and the Museum of New Mexico collaborated with the Indian Arts Fund and the New Mexico Association on Indian Affairs to create a juried exhibit of traditional Indian arts. It was to be held in conjunction with the long-established annual Fiesta celebration.

The first exhibit opened on September 4,1922, under the title of The Southwest Indian Fair and Industrial Arts and Crafts Exhibition and was more colloquially known as The Indian Fair.

While the Fiesta celebrations took over the Plaza, the entire Indian Fair exhibit was displayed in the National Guard Armory Building, behind the Palace of the Governors. Admission fees were charged to the visiting public.

Events included the display of Native American dancing, singing, Native dress, and demonstrations on jewelry, pottery making, and bow and arrow contests held on the museum patio.

Indian Fair 1922. Patio of the Palace of the Governors. Kenneth Chapman center with Santiago Naranjo. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives.

Indian Fair 1922. Patio of the Palace of the Governors. Kenneth Chapman center with Santiago Naranjo. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives.

A handful of museum curators, including Chapman, judged the various categories, which were named for each of the participating pueblos. Each category was awarded a first prize of $5 and a second prize of $3. There was also a $15 prize and a trophy awarded for “Best Tribal Display”. The Museum staff acted as intermediaries in selling the art to the public. The artists received their money after the Fair was over.

For five years the Indian Fair remained in the Armory and the Palace of the Governors courtyard patio during Fiestas.

In 1927, the Museum of New Mexico ended their involvement with both the Fiesta and Indian Fair events. Kenneth Chapman founded an independent committee to continue supporting the advancement of traditional Native arts and the Fair. The Southwest Indian Fair Committee included Hewett and dedicated Native heritage supporters Amelia and Martha White, Santa Claran day-school teacher Lucy Bacon, Dorothy Stewart, Margaretta Dietrich and others.

From 1927 to 1931, the Fairs continued to be held in the Armory building and on the patio of the Palace of the Governors during Fiestas. The Committee also provided transport from the pueblos, camping equipment, and food for the Fair participants totaling approximately $400 a year. These costs were covered by admission fees, along with a small percentage added to the sales price of the exhibit items.

Committee members would agent the sales of all items and Native participants continued to wait until the Fair was over in order to receive their payment. The average price for a pot was $3. The sale of the now legendary Maria Martinez’ pots would bring as much as $11. At a time when a can of milk cost 10 cents, coffee was 35 cents a pound, and a pair of men’s britches could be bought for $1.75, these earnings were considerable.

To ensure display of excellent works, Chapman went to pueblos in advance of the Fair and buy those pots and items he felt represented the best of the art form. He would spend in the range of $400-$470 annually from monies donated by the committee members and other supporters. These purchases also served to increase value and encourage the enthusiasm of the artists to continue their works and high quality standards.

After 1931, the Santa Fe Indian Fair stopped.

The Committee took the exhibits on the road.… In 1934, the SWIFC were taken over by the Arts and Crafts Committee of the New Mexico Association on Indian Affairs. By 1935, participation by the Native American artists was waning. In 1936, NMAIA President Margaretta Dietrich proposed bringing the Fair back to Santa Fe and again hold it during Fiestas…

The first of the Saturday Indian Markets was held July 11, 1936. Participation was strong. Seventy-five to 100 people arrived from the Pueblos of San Ildefonso and Tesuque. The artists would do their own selling, thus eliminating the third party and the wait for payment, and allowing for direct connection between vendors and buyers. As the weeks continued, the Market was so successful that the artists would return to sell their work and that of their family members. This caused a spread of displays inching their way down the Palace’s neighboring streets.

Although there were many categories of works sold, pottery was one of the most popular. The average weekly sale of pots by such prize-winners as Maria Martinez and Severa Tafoya was $16. Those who were less skilled earned in the range of $4-$6 per week. Public attendance was estimated to be in the range of 8,000 for the entire summer.

Chabot had helped establish the freedom for the artists to set their own prices and the Markets’ success brought financial independence to many of them. In an interview by the Santa Fe New Mexican in 1996, Chabot recalled that at the end of the summer of 1936, Maria Martinez told her that “eight girls got water in their house.”

Even after the Markets were over, vendors continued to come to Santa Fe to sit under the portal of the Palace of the Governors. To this day, it is a highly anticipated experience for many visitors to Santa Fe to visit Native vendors and artists under the Palace’s portal….

By 1959, the future of the NMAIA and its organization of the Market was in doubt. Fortunately, Al Packard… took on the cause. Packard and other prominent figures supported the NMAIA in bringing organization to the Market and reviving the juried exhibits and prizes. Efforts became entirely focused around the extensive organization of Indian Market.

The 1960s brought a renewed national interest in Native American culture, which helped the cause considerably. In 1962, the Market was held the weekend preceding Fiestas, establishing its independence from any other event. Gradually, throughout the Sixties, more and more rows of booths were installed for vendors….

By 1980, 330 booths were provided. In 2002, 625 booths enabled the participation of as many as a thousand artists…As the 92nd Annual Indian Market draws to a close in 2013, as many as 220 tribes from the U.S and Canada participated, over 600 booths lined the Plaza and surrounding streets, as many as 68 judges determined winners in over 3,600 category classifications and awarded over $110,000 in prizes. More than a thousand artists attended. The white roofs of vendor booths line the streets surrounding the plaza and stretch for many blocks.

Now, the Market is usually held during the third weekend of August. Vendors make their way to Santa Fe from all directions, some of them bringing delicious Native foods to sell to an eager public….

Cavan Gonzales, Maria Martinez’ great-grandson, has been working on his collection of pots since late last year. He has won many awards over the years, and he relies on the sale of his pots for much of his family’s annual income.

The judging process upholds its original rigorous standards of evaluation of excellence in cultural aesthetics, quality and creativity in all of the category classifications….

Within Santa Fe’s historic town center, hundreds of Native cultures converge – creating a proud and spectacular display of color and beauty. There is a tremendous amount of history, tradition and religious ceremonial information to be gleaned from each costume. Almost every detail has a purpose and meaning that is intricately woven through complex Native lineages.

For more information on Indian Market and SWAIA go to: http://swaia.org/.

For help planning your visit to Santa Fe, go to: http://santafeselection.com/.”

Neenah Payne writes for Activist Post and Natural Blaze

Become a Patron!

Or support us at SubscribeStar

Donate cryptocurrency HERE

Subscribe to Activist Post for truth, peace, and freedom news. Follow us on SoMee, Telegram, HIVE, Flote, Minds, MeWe, Twitter, Gab, What Really Happened and GETTR.

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.

Be the first to comment on "100 Year Anniversary of Santa Fe Indian Market"