By Sam Jacobs

By Sam Jacobs

“It is not often that nations learn from the past, even rarer that they draw the correct conclusions from it.” – Henry Kissinger

American students are notoriously bad at geography, and have been for some time. In 2002, for instance – the year after the 9/11 attacks – only 17% of American students could find Afghanistan on a map. In 2016, less than one third were able to score a minimal pass of 66% on the National Geographic Global Literacy Survey. In 2015, the United States Government Accountability Office reported that 75% of eighth grade students don’t even know what geography is.

Picture your old-school geography class. More likely than not, it was a boring subject requiring rote memorization of global factoids, U.S. state names, and their capitals. This does American students a disservice, because an appreciation for the hidden power of geography helps one make sense of seemingly random historical tidbits, more accurately predict the future, and see beyond political rhetoric to what actually matters among nation-states.

When contemplating geography’s usefulness in better understanding our world, consider the following:

- Why is it important to the state to get a handle on its subjects and their environments, i.e., through long-established practices like land registries and the creation of permanent last names? Or more recent examples such as the census bureau, the passport system, the DMV, birth and death certificates, or just registering to vote?

- Why is the state seemingly always the enemy of “people who move around,” i.e., nomads and pastoralists, hunter-gatherers, Gypsies, vagrants, homeless people, itinerants, runaway slaves, and serfs? All have always been a thorn in the side of the state, and efforts to permanently settle these mobile peoples seem to rarely succeed.

The answers to these questions are straightforward when the classic imperatives of the state are known – and these are taxation, conscription, and the prevention of rebellion.

In order to satisfy these imperatives, the state has to know as much as possible about its inhabitants, and it wants them to be sedentary. You can’t tax what you can’t measure. You can’t draft someone to fight if you don’t know they exist. And you can’t stop a rebellion if you don’t know those who seek to overthrow your order.

As a result of these imperatives, accurate maps of the land and the people that occupy it are necessary for the survival of the state. And what’s in those maps is as important as what’s excluded from them.

Geography’s raison d’etre is straightforward: to write about, describe, or better understand patterns and processes on Earth. It’s not just maps and state capitals, nor is it simply the creation of maps (that’s cartography).

Thus, when the hidden power of geography is appreciated – especially as it relates to the state’s imperatives – conflicts between competing states as well as the relationship between the state and the individual begins to make more sense.

Early Geography: The Printing Press and “Imagined Communities”

To begin with a basic concept of geographic history, it’s important to consider the difference between a nation and a state. It is common today for the term “nation” and “country” to mean the same thing, but in geography, “country” actually means “state” and the term “nation” is defined by a shared identity among a large population within a state.

To begin with a basic concept of geographic history, it’s important to consider the difference between a nation and a state. It is common today for the term “nation” and “country” to mean the same thing, but in geography, “country” actually means “state” and the term “nation” is defined by a shared identity among a large population within a state.

This shared identity is what Benedict Anderson referred to as “imagined communities.” These communities of the imagination had early relationships to the invention of the printing press, which allowed people (other than elites) to have easier access to both maps and literature. Such publications contributed to standardizing languages, which allowed a variety of cultures to understand not only each other, but also the maps that explained the world.

The printing press contributed to standardizing the histories of the past so that many different cultures began to remember (and forget) the same things. According to Anderson, communities became imagined because people of even the smallest nations will never know or interact with the majority of people in that country. Yet, the majority will have an understanding of their shared histories.

From the Western perspective, the early history of geography has its origins during the Middle Ages. European travelers would explore beyond the edge of known territory and map their observations of different places, races and cultures. A common similarity of these early written accounts was that different types of climate were thought to be a defining factor for how races and cultures were different from the European traveler.

These early accounts were written from the perspective that European travelers were normal, and all non-Europeans were then defined by their difference. This is to say that according to these written accounts, Europeans were the reference point for what was normal and right.

During this period, the climates of the world were classified by three types: frigid (very cold), temperate (just right), and torrid (very hot). The frigid climate was thought to be too cold for people while the torrid climate was too hot. This understanding of the climate is why, for example, Ethiopians were thought to have lived too close to the sun, and that their skin was burnt black as a result – an observation considered a scientific fact because the European traveler was able to see it with their own eyes and then write about it.

An important aspect to these early written accounts was that as new cultures, terrain and races were “discovered,” they were often described as monsters from inhospitable lands. These monsters were commonly written about and became a source of both myth and legend. Such legends told of monstrous beings at the edge of where the known and unknown territories meet.

As these early Europeans embarked on new expeditions, each exploring further than the last, the unknown territories became known, but the monsters were always pushed further to the edge of the updated maps. According to Joanne Sharp, this pattern was a result of two factors.

First, the Europeans had a need to define their territory with myths and legends of the unknown monster because this was a defining factor for European identity. This is to say that an identity is not only based on how people are similar, but also how people are thought of as different.

The second factor was that for the earliest explorers during this time period, first contact and interaction with new cultures did generate fear. Sharp noted:

Practices of lip stretching and yoga could seem like distorted bodies to the first travelers; warriors’ use of colorful shields might look – from a distance – like faces on their chests; and non-European languages could sound very alien to travelers.

It was through these early expeditions that the Middle Aged maps of the world had a large influence on how people understood that world, and their place in it.

Roots of Geopolitics: From the Monarchy to the State

The transition from the Middle Ages to the 17th century is not marked by a single event, but rather several events over long periods of time. One of the more discussed events was the transition from the monarchy to state sovereignty, a move that marks the early origin of geopolitics.

From 1618 to 1648, one of the most destructive wars in history was waged in Central Europe. At its end, the “Thirty Years’ War” marked the creation of state sovereignty with the “Peace of Westphalia” settlement in 1648. This peace settlement defined territories by state sovereignty rather than a territory, and everything in it, owned solely by the monarchy. Sovereignty is the cornerstone of statehood and is defined by four basic principles:

- Defined boundaries of state territory.

- A government structure with absolute authority over internal and external affairs.

- Recognition by other states.

- A permanent population in that territory.

An important aspect to state sovereignty was that the population of a territory was no longer the property of the monarchy. A state relies on its territory as the source for political organization, but this became problematic because people who lived in those territories also had a new found freedom. They were no longer serfs, or considered property owned by the king, but now viewed as citizens of the sovereign state.

Similar to the previous example about monster myths being a political tool toward defining a European identity during the Middle Ages, maps and supporting literature played an essential role in not only marking a state’s territory, but also the imagined community of people inside and outside of that territory.

Prior to the rise of state sovereignty, loyalty to the monarchy could be an issue, and more so for the kings’ armies. It was not uncommon for these early armies to be made up of thieves and vagabonds as well as contracted mercenaries. These types of soldiers had little to no loyalty to the king, which was problematic for several reasons, one of which was because they were armed. Following the 1648 peace settlement, loyalty became tied to nationalism and the country.

This was an important development because, as mentioned, defining an identity results from shared similarities as well as differences. The expansion of territory through war could be more easily acceptable to the soldier if the enemy was different. However, when the enemy looked more like a friend, as can be found in any historical example of dueling Christian armies, the power of the state together with the nation changed the notion of territorial expansion from the “sport of kings” to a clash between nations.

Geopolitics, Social Darwinism, State Survival, and “Lebensraum”

These histories serve as a simplified starting point for understanding geopolitics, and the types of influences that are embedded in the concept. With state sovereignty came the dominant understanding that a state’s purpose was that of survival. Said differently, states were seen to always be in competition with different states.

These histories serve as a simplified starting point for understanding geopolitics, and the types of influences that are embedded in the concept. With state sovereignty came the dominant understanding that a state’s purpose was that of survival. Said differently, states were seen to always be in competition with different states.

In the late 19th century, Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection was being applied by scholars to the study of societies (Social Darwinism). German geographer, Friedrich Ratzel, applied Darwin’s natural selection theory to state sovereignty (particularly Germany), and together the concept became known as the “Organic Theory of the State.”

The foundation of Ratzel’s theory was that states interact with different states through the “survival of the fittest” perspective, and that a state must grow through territorial expansion in order to thrive.

The implementation of this theory had a particular consequence. Ratzel’s theory of state survival is said to have legitimized “continual war of all against all, as each country must seek the path of the least resistance to territorial expansion and must simultaneously defend its territory at all costs.”

The term “geopolitics” was coined by Swedish political scientist Rudolf Kjellen (a student of Ratzel’s) in 1899, and inspired an intellectual movement between German and Scandinavian scholars. This movement, supported by the “science” of geopolitics, resulted in a veneer of legitimacy that a state, and its nation, should be viewed as combined elements that together produce a stronger effect.

Ratzel envisioned the nation and state relationship as a “super-organism” whose strength was determined by the size of its territory, population, and the availability of natural resources. Ratzel further published The Sea as a Source of Greatness of a People in 1901, and identified ways in which the land and sea provide opportunity for expansion. This work introduced the concept “Lebensraum,” translated to mean “living space,” which argued that stronger states would naturally take territory and resources from weaker states.

Prior to World War I, Ratzel and Kjellen’s work contributed to the idea that Germany was the “land of geographers,” as German universities were among the first to teach geography. This renewed interest, supported by such geopolitical theories, positioned geography as the “god’s eye view” of how the world “really” worked.

The Nazi Connection: Geopolitk and Hitler’s “Mein Kampf”

The relationship between geopolitics and the rise of the Nazi party is accredited to political geographer Karl Haushofer. Prior to Haushofer’s career in “Geopolitik,” he was active German military who spent time in Japan studying their armed forces between 1908 and 1910. Haushofer’s interaction with both military officials and scholars during that time would later be accredited to the rise of geopolitical institutions in Japan during the 1920s and 1930s. His influence would also stretch as far as South America.

Following World War I, Haushofer retired as a major general in 1919, and took a professor position teaching geography at the University of Munich. Haushofer, like Ratzel before him, believed that German greatness was dependent upon Lebensraum:

If the state was to prosper rather than just survive, the acquisition of ‘living space,’ particularly in the East, was vital and moreover achievable with the help of potential allies such as Italy and Japan.

According to Haushofer, if Germany was to grow into a world power, and rebound from the losses of the WWI defeat, its leadership would need to be thoughtful of five essential elements:

- Physical location

- Resources

- Territory

- Morphology

- Population

Haushofer’s own geopolitical theories promoted the concept of “pan regions,” which argued that Germany and other state powers, such as Japan, should develop distinct geopolitical strategies that focus on separate regions. To do so was to carve up the map and become neighbors in world domination rather than interfering within each state’s territory of interest. For Haushofer, his geopolitical focus was to the East and Africa.

Following the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, Rudolf Hess (Hitler’s personal secretary, and one of five people who held key positions in the Nazi party), was arrested and imprisoned for participating in the failed coup against the Weimar Republic. Hess was a former student of Haushofer, and it was this relationship that would lead Haushofer to visit Hess in prison, thus becoming introduced to Hitler.

As we are familiar, Hitler authored Mein Kampf while in prison, and the work draws from the theory of Lebensraum (living space) to support Hitler’s vision of German destiny, territorial expansion and “the master race.”

Some common misconceptions around this history (especially in America) are that Haushofer was thought to be the intellectual powerhouse behind Hitler’s ambition of territorial expansion and genocide. It is true that Haushofer was highly influential with ambitions of territorial expansion, but it was Hitler who placed the far greater emphasis on the identity of people – i.e., the master race vs. the Jewish monster.

Haushofer was never a Nazi himself, and his son had been executed in 1945 for his role in a bomb plot to assassinate Hitler the year prior. With learning of his son’s role in the assassination attempt, Haushofer would commit suicide in 1946.

It is also a misconception that Hitler manifested the hatred of the Jewish people on his own. This claim is not to undermine Hitler’s role in the atrocities of WWII, but it is useful to explore the longer history of persecution and violence against Jewish people in this part of the world long before Hitler was born. In this way, it becomes more useful for understanding geopolitical concepts to recognize the ways in which Hitler “tapped” in to preexisting prejudices and manipulated identities as to justify territorial expansion and genocide.

The Decline of Geopolitics

There were several theoretical and scientific concepts that shaped the thoughts of world leaders leading up to and during WWII that are commonly associated with the Third Reich. Some examples include propaganda (Himmler), the systematic approach to genocide (Fordism), and eugenics to only name a few. However, none of these examples originated with the Nazis, and geopolitics is no exception.

There were several theoretical and scientific concepts that shaped the thoughts of world leaders leading up to and during WWII that are commonly associated with the Third Reich. Some examples include propaganda (Himmler), the systematic approach to genocide (Fordism), and eugenics to only name a few. However, none of these examples originated with the Nazis, and geopolitics is no exception.

Geopolitics did play an integral role in the rise of the Third Reich, but following the Allied victory of WWII, geopolitics was seen as an “intellectual poison.” With few exceptions after 1945, geopolitics was tainted with Nazism and lost credibility in the United States, Britain, Russia, Japan and other parts of Europe.

In relation to Haushofer’s early influence stretching to South America, Lebensraum and theories of the organic state were alive and well in South American military strategy post-WWII. Geopolitics later reemerged in the West during the 1970s, due to Henry Kissinger making sense of the Cold War.

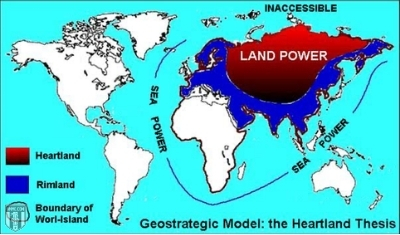

The focus in this article is only a small snapshot of a particular geography and its history in relation to a single geopolitical theory. Other influential theories around this period include U.S. Admiral Thomas Mahan’s classic on sea power, and Halford Mackinder’s “The Heartland Theory.”

Mahan’s theory on sea power suggested that the Navy was the most important factor in projecting state power (Japan found this useful), and Mackinder believed that world power was not obtainable through the sea, but through the control of the Eurasian landmass with the anticipation of a rising Russian power.

There are also many other political geographies that justify the use of violence that include imperialism, both British and Spanish colonialism, and even earlier empires. Our focus here is only one of many examples. However, there are some important geographic concepts which can be taken away from this.

The Hidden Power of Maps: What’s Included (and What’s Not)

Maps are an important aspect of geography, and they all have hidden forms of power. As can be found in the earlier discussion of “imagined geographies,” it’s important to be aware that all maps (the same goes for all media today) have a creator that – either knowingly or unknowingly – projects what they value and find important onto their creation.

As such, it is always useful to be aware of what types of places, history or knowledge is not on a particular map. While we know that what is on a map is certainly useful, what is not on a map can be much more important if we are interested in charting a course to better understand the power of geopolitics.

Environmental Determinism: From Ancient Greece to Rural Appalachia

A common theme embedded in these early geopolitical theories is traced back to the Greeks, who speculated that human behavior is shaped directly by climate and geographic location. This type of thought is known as environmental determinism. Scholars who take a deterministic view suggest that intellectual advancement in Greece was a result of the mountainous landscape that inspired “loftier thoughts.” The same concept has been applied in America because our wide open plains inspire people to “think big.”

If only human behavior was this simple. The problem with the environmental deterministic view is that it suffers from a lack of attention to types of government structure, laws, history, social dynamics, coercion, violence and types of technology that also shape human behavior. While the environment does play a part, it is only a small part of a much larger process of how human behavior is shaped. Not to mention that today, the environment is no longer understood as “nature” or the “natural” world, but also includes human-built environments (urban spaces). When clearly defined, environmental determinism is too simple of an explanation to be useful.

As an example, the American southern accent (think the TV show Hee Haw) can often be associated with the thought that rural people are unintelligent. However, as can be found in the work of John Gaventa, this common stereotype has its origins in a corporation violently exploiting people in the Appalachian Valley and framing their culture as too simple-minded to understand capitalism. This example is interesting in several ways because Appalachia is mountainous, but the “loftier thoughts” that attempt to explain how the Greeks were intellectually advanced is absent in this context.

Perhaps a more recent example of environmental determinism can be found in this news article that attempts to describe “white nationalism” as a characteristic of all firearm owners. According to this narrative, people who own firearms are white, violent, and are said to be on a level similar to Islamist extremists. As we know, there are many different cultures and races that understand the importance of firearm ownership.

However, this current narrative is geopolitical at its core, and has elements of every concept contained within this article. We have imagined geographies (includes both shared and forgotten histories), a strong emphasis of identity (us vs. them), a stripped-down version of Lebensraum (tying up the nation and the state for ideological expansion, rather than geographical), and the environmental deterministic view that attempts to simplify and single out a particular race.

It should also be noted that environmental determinism is commonly discussed in ways that focus on how non-white races are repressed. Many of those discussions are absolutely valid and true. Nevertheless, our focus here is not to marginalize those repressions, but rather highlight how such deterministic views do not discriminate in their political use. Environmental determinism has impacted all races and cultures in one way or another.

Applying Geography

At the outset, we posed the question: Why do so many people not know what geography is all about? The answer to that question is perhaps because geography has such a long and violent history in the project of state creation and civilization.

At the outset, we posed the question: Why do so many people not know what geography is all about? The answer to that question is perhaps because geography has such a long and violent history in the project of state creation and civilization.

Thus understanding the value of geography helps us see the state’s imperatives – taxation, conscription, and the prevention of rebellion – for what they are. It also helps each of us better orient our relationship to the state: What information we divulge to it, whether that be for a gun background check or an income tax return. What state policies (up to and including war) we support. And why politicians say one thing and regularly do another.

Geography also provides an opportunity to place seemingly random histories under a microscope – to question and better understand why certain patterns and processes shape how we understand the world, and our place in it.

While some believe that geopolitics declined following WWII, later re-emerged and declined yet again with the Cold War, geopolitics is very much alive and well today. The maps of the world are still being carved up, and states are still in competition with one another either overtly or in more subtle ways.

For American foreign policy in particular, this is evidenced where the U.S. military maintains foreign bases, to whom the military-industrial complex is permitted to sell American-made weapons, why Washington orders drone strikes in certain places and not others, among many others.

Geography can certainly provide a clearer understanding of potential futures, because states have been playing by the same basic rules since the rise of state sovereignty in 1648. The better we can understand these geographic histories and the maps that define them, the better equipped we become at making sense of seemingly random occurrences throughout the world.

Source: Ammo.com

Subscribe to Activist Post for truth, peace, and freedom news. Send resources to the front lines of peace and freedom HERE! Follow us on SoMee, HIVE, Parler, Flote, Minds, and Twitter.

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.

Be the first to comment on "Geopolitics: How Maps Help Us Understand History, Predict the Future, and Go Beyond Politics"