By J.P. Koning

By J.P. Koning

For centuries bank deposits have come with a comforting guarantee. Depositors have always been able to quickly convert them at par into cash.

But this guarantee is slowly being eroded. Banks in Canada, Ireland, Australia, Denmark, and Sweden are closing full-service branches and adopting a less-staffed “cashless bank” model. In a cashless branch, customers can no longer deposit or withdraw cash over the counter.

The next step will be when banks remove their external ATM machines too. Once this happens, we’ll have entered a strange new world where bank deposits are permanently inconvertible.

But if we don’t want a world with cashless banks, here’s a potential solution. Maybe banks should be allowed to issue their own unique brand of banknotes. By doing so, bankers may have more of an incentive to promote cash availability.

Bankers have been steadily introducing cashless banks over the last few years in response to falling customer demand for cash. With fewer people wanting to withdraw or deposit cash, the cost of offering these services gets harder to justify to shareholders.

Some commentators worry that banks are not simply reacting to customer preferences but are taking an active role in reducing cash usage. In a recent opinion piece, Brett Scott accuses banks of nudging customers away from cash by re-designing the withdrawal and deposit processes to be less accommodating.

As Scott points out, banks have an incentive to move customers into cards and other digital channels because that way they can make more profit off of transactions and suck up more data. Furthermore, deposits compete with central bank-issued banknotes as a form of saving. Banks prefer that consumers lodge cash at the bank because deposits are a low-cost source of funding for banks.

That banks are sole distributors of a third-party product that they directly compete with represents a major conflict of interest. This arrangement is unfortunate given cash’s many benefits. To begin with, it makes for a great back-up payments system — unlike card-based systems, cash can’t crash. It is also used by many people for budgeting purposes. And finally, banknotes allow people to regulate how much personal information they must give up in transactions. I’ve talked about many of these advantages before.

Given that cash is important to society, but banks have a perverse incentive to prevent its circulation, what is the solution? Perhaps the answer is to get banks on side by allowing them to issue their own banknotes. If they have a direct financial stake in the fate of cash, then banks will be less conflicted in the role they play as society’s main distributors of coins and banknotes.

Ireland is an interesting case study. The Bank of Ireland is the largest private bank in both the Republic of Ireland (a separate country) and Northern Ireland (which is part of the UK). Oddly enough, even as the Bank of Ireland threatens to make most of its branches in the Republic of Ireland cash-free, the northern arm of the bank is rolling out new polymer banknotes in 2019.

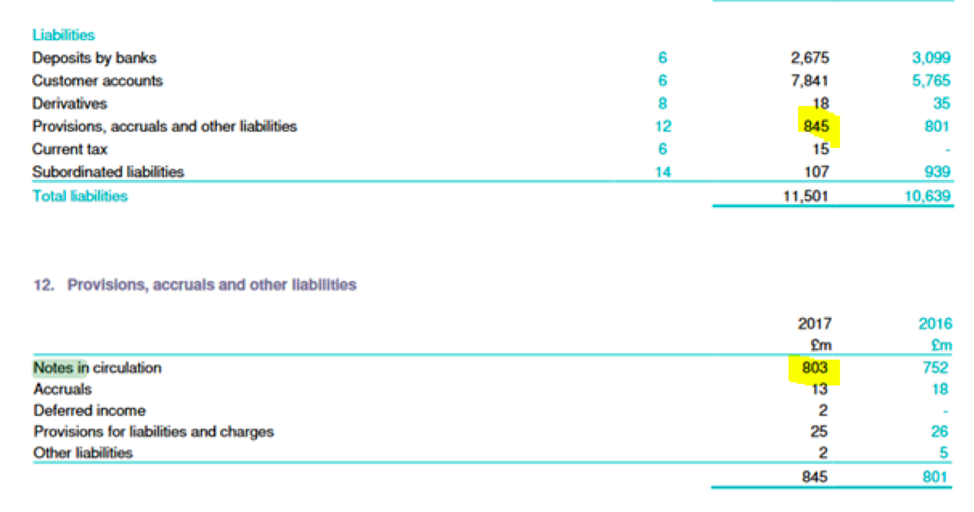

Banks in Northern Ireland and Scotland enjoy a long tradition of issuing their own banknotes. Of the four note-issuing banks in Northern Ireland, the Bank of Ireland is the largest issuer followed by Ulster Bank, Danske, and First Trust. As of the end of 2018, the big four had issued £2.9 billion worth of banknotes. These banks aren’t obligated to provide Northern Ireland with cash. They print it because their customers want it.

The Bank of England, UK’s central bank, requires Northern Ireland’s private note issuers to “back” each pound they issue with at least 60 cents in Bank of England notes or coins. The other 40 cents in backing can be held in an interest-yielding account at the Bank of England.

The Bank of England, UK’s central bank, requires Northern Ireland’s private note issuers to “back” each pound they issue with at least 60 cents in Bank of England notes or coins. The other 40 cents in backing can be held in an interest-yielding account at the Bank of England.

Northern Ireland’s cash-issuing banks thus enjoy two advantages relative to banks that cannot issue cash. Since they needn’t pay any interest to their banknote customers, but enjoy interest on the backing assets held in their account at Bank of England, they earn a recurring flow of income on each note that they put into circulation. Secondly, the circulation of their particular brand of banknotes serves as a form of free advertisement. The more of its notes that a bank can get the public to use, the more visibility it steals from competitors.

Thus, the Bank of Ireland’s northern operations have an incentive to ensure that cash is always available to depositors. But the bank’s southern arm, which distributes euro banknotes, does not have the same incentive, since it doesn’t directly share in the financial advantages of promoting cash usage.

The benefits of issuing cash can be sizable. For instance, at the end of 2017 Ulster Bank has issued £803 million in banknotes. This accounts for 7% of the bank’s total £11,501 million in liabilities. Given that Ulster Bank currently pays as much as 0.85% on its other liabilities, including savings accounts, the ability to issue notes at 0% significantly reduces its funding costs. I doubt that Ulster Bank would want to sabotage this gift.

Critics will point out that allowing banks to issue cash comes at the expense of the tax payer. That’s true. All of the profits that the Bank of England earns are paid back to the state, and ultimately the taxpaying citizens. By directing a bit of interest to the Bank of Ireland and other private issuers, that leaves less for the state.

Critics will point out that allowing banks to issue cash comes at the expense of the tax payer. That’s true. All of the profits that the Bank of England earns are paid back to the state, and ultimately the taxpaying citizens. By directing a bit of interest to the Bank of Ireland and other private issuers, that leaves less for the state.

But notice that Bank of England strikes a careful balance. It only allows the Bank of Ireland, Ulster Bank, and other private issuers to keep 40% of their backing assets in an interest-yielding account, the other 60% being lodged in no-yield Bank of England banknotes. So the current Northern Irish arrangement illustrates how it is possible to accommodate both taxpayers, banks, and their customers.

Alternatively, banks could invest the 40% in a higher yielding loan portfolio. Although some people might have financial stability concerns, we know from Selgin and White’s explorations of free banking that private banknote systems can be quite sound.

Allowing private banks to issue banknotes may seem like a radical solution. But by fixing the dysfunctional relationship between banks and cash, this option may help prevent an equally radical scenario from emerging; a world with only cashless banks.

Sign up here to be notified of new articles from J.P. Koning and AIER.

J.P. Koning is a financial writer and blogger with interests in monetary economics, economic history, finance, and fintech. He has worked as an equity researcher at a Canadian brokerage firm and a financial writer and publisher at a large Canadian bank. More recently, he has written several papers for R3, a distributed ledger company, on the topics of central bank cryptocurrency and cross border payments. He founded the popular blog Moneyness in 2012. He designs economics and financial wallcharts at Financial Graph & Art.

This article was sourced from AIER.org

Be the first to comment on "The Rise of Cashless Banks (And What To Do About It)"