Jason Kaspar

Activist Post

In the last thirteen years, a new financial order replaced capitalism in America. With cat-like tread, this transformation has caught most Americans unaware, let alone some of country’s best financial minds (many of them fascist anyway).

This new order constitutes the socializing of risk, a concept I have termed: Sociapitalism.

Sociapitalism is different than Social Capitalism – a European concept. Social capitalism is the redistribution of wealth through social programs, such as unemployment benefits, food stamps, and government housing. Sociapitalism is not a redistribution of wealth, but a redistribution of risk. The government transfers risk from one entity to the system, securing the safety of the entity.

Social capitalism allows corporate failure. Sociapitalism does not, reducing the only possibility of failure to the sovereign state.

For the most part, our country was founded on the principle that success or failure should be predicated on one’s own merits. The weak died, the strong survived. Depressions and recessions cleansed the system, firming up the foundation for the next economic advancement. Capitalism brought corruption – true – but that corruption was eventually punished with failure. Failure distinguishes capitalism from all other economic systems.

That model has changed, and it became visibly apparent in 1998 when the government orchestrated the bailout of Long Term Capital Management. In hindsight, this intervention may have been the biggest mistake in American financial history. If Long Term Capital Management would have failed, Lehman Brothers would have likely failed at that time, and the United States would have fallen into a recession. Positively, the United States would have averted an equity bubble, Glass Steagall would have never been repealed, and the system would have been cleansed from the froth of the late nineties.

Instead, the orchestrated bailout of Long Term Capital Management ushered in the biggest equity bubble (in terms of valuation) in the history of the United States. The collapse of this tech bubble did wipe out large deposits of wealth, but valuations never corrected to the long term historical mean because the U.S. government buttressed the system by creating a private debt bubble. This intervention served to bail out the equity collapse. The private debt bubble instigated a handful of asset bubbles primarily centered on real estate.

In 2007, as we all know by now, this real estate bubble finally began to deflate, taking much of the private debt bubble with it, and forcing a collapse of the entire private market – equity and debt. The private market needed to collapse; it needed the long overdue cleansing it did not receive in 1998 or in 2003. Instead, beginning in 2008, the biggest government intervention in U.S. history prevented the market cleansing once again, and it has subsequently led to the final bubble – the government bubble.

Like the private debt market bubble which supported equity valuations, the government bubble is now propping up equity market valuations and the private debt market. I fully realize that the world would be in a full depression had the United States not intervened, but I firmly believe the consequences of the latest intervention will only prolong and increase the inevitable misery. At each interval, the ante has increased; the pressure has been notched ever higher. The U.S. needed a slight recession in 1998; in lieu of that recession, the country needed a severe recession in 2002; without that severe recession, it needed a depression in 2008.

Now, the system has been put at risk.

Over the last two years, the government has supported virtually every private sector function. Through extension of unemployment benefits, home buying tax credits, cash for clunkers, build America bonds, quantitative easing, and myriad other programs, the government has propped up the private sector. Once the support structure surpasses the point of sustainability, the private sector will likely collapse along with the system. Where previously an American business’s success had been self-determining, its success is now predicated upon the outcomes of the domestic collective. This risk is pervasive; a family owned restaurant in rural Texas, muni bonds, government bonds, equities, commodities, a new venture in Vietnam . . . all share in the risk of the collective.

As an example of how the economic model has changed, my great-great-grandfather started a manufacturing company in 1898 that employs to this day hundreds of Americans. It has survived because of successful calculations in business risks and a robust understanding of the business cycle. Its tenure spans twenty recessions, one depression, two world wars, oil embargos, steel shortages, and twenty presidential administrations. It has achieved its longevity largely by avoiding debt and making very conservative business decisions.

One hundred and thirteen years later, the company’s future depends almost strictly on forces outside its control. It now shares risk with companies like Citigroup, Wachovia, Wells Fargo, and General Electric, since the risk of these companies has been transferred to taxpaying entities through massive government leveraging. Not only is this redistribution of risk anti-American, it is potentially hazardous to the whole because of coupling in the system. Historically, if a company failed, there might be losses, but American capitalism contained the damage. Capitalism acted like an emergency brake on an assembly line.

Conversely, the government has created an environment where excess risk is allowed to flourish without penalty. Now we have a new bubble, a government bubble; one that will end all bubbles for decades to come.

Homebuilders: A Prime Example

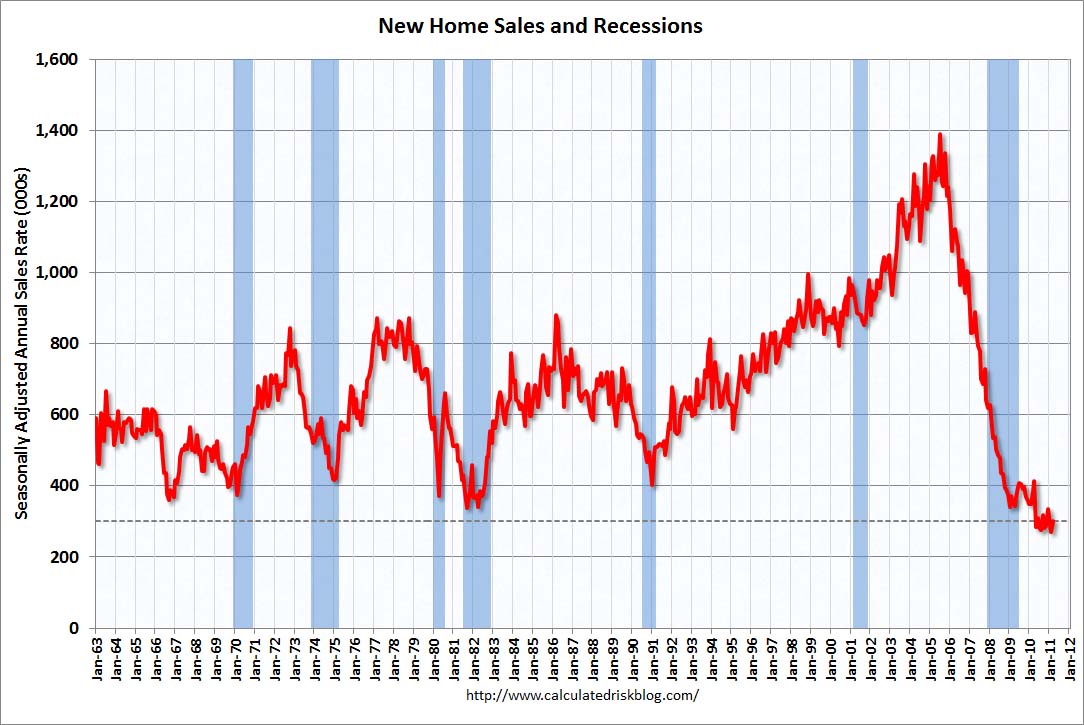

Yesterday, the Census Bureau reported New Homes Sales on a seasonally adjusted basis. The first three months of this year witnessed the fewest home sales since 1962, the first year records were kept.

One might conclude that stocks of homebuilders would approach the historical lows of the last ten years, or have at least bottomed six months ago anticipating this might be the worst print. Not only has housing not bottomed, homebuilders are instead UP over 100% since their lows in November of 2008 and March of 2009. You can see this in the XHB etf (XHB also has building suppliers and retailers such as Home Depot). The system has salvaged companies like Hovnanian from the brink of Chapter 11. No longer is the mantra “only the strong survive” accurate, because weak companies have been pampered, accommodated, and allowed to flourish, creating over capacity and driving up risk across the system.

In my office, I have 75-page annual reports of Hovnanian, Toll Brothers, and DH Horton – three very large U.S. homebuilders. The reports are irrelevant; worthy of a good ol’ fashioned Texas bonfire. What matters is how far the U.S. government allows the homebuilders to extend tax losses backwards, how the U.S. government will support interest rates by keeping them artificially low, and what kind of home buying tax credit the U.S. government will offer its home buyers. System support now determines future success, and stock prices are uncorrelated to financial statements.

Investing Implications

What this means for investors is that valuations are presently converging. The riskiest companies/assets are individually worth more because their risk has been diluted. They have offloaded the risk with the safest assets, which in corollary means that the safest assets are intrinsically worth less. Netted together, the valuations should be substantially diminished when taking into account the coupling. Nevertheless, liquidity – and money managers whose careers began in the eighties and nineties when you always bought – have blinded the market.

Secondly, historically the majority of an asset’s risk has been unique to that asset. Now, many companies and many industries collectively share the majority of an asset’s risk. In years past, investing legends made fortunes by studying an individual asset and determining that its risk was mispriced. They were great handicappers. I believe that sociapitalism has rendered this skill inconsequential. There may be some mispricing on individual assets, but it is far outweighed by the mispricing of the risk connected to all assets, which means that all assets are overpriced in real terms.

Thirdly, the implications of the government bubble are dramatically different than those of previous bubbles. Since the risk is systemic, it is inherently impossible for asset owning investors to avoid it. When investors discovered that something was amiss with Bernie Madoff, they invested elsewhere through the thousands of other investment options. Likewise, during the equity bubble in 2000, an investor could diversify into other assets besides overpriced tech stocks. Today there are few, if any, viable alternatives.

Finally, when the risk is repriced, the only way to benefit is to bet directly against the group risk. There are very few vehicles for this purpose and even fewer for those who do not have tens of millions of dollars. Additionally, the U.S. government continues to blame market participants who anticipate the fallout, and its actions limit the ability for these participants to benefit from a repricing. The government is trying to ensure that there are no winners, while finding a scapegoat for its own sins.

When the government bubble pops, America will be changed forever.

Jason Kaspar is the Chief Investment Officer for Ark Fund Capital Management, focusing on investment and portfolio management. This article first appeared on Gold Shark.

Be the first to comment on "Sociapitalism: How the Government Became the Next Bubble"