By Sam Jacobs

By Sam Jacobs

While there are some in the United States who believe we are headed toward another Civil War, there is perhaps another, more recent parallel worth exploring – the so-called “Italian Years of Lead.”

The short version is that in the late 1960s through the early 1980s, Italy was a hotbed of assassination, shoot-outs and bombings between various factions of the far-left, the far-right and the Italian government – with American, British and Soviet intelligence agencies often pulling the strings.

While the death toll was a lot lower than it could have been, it’s a fascinating and oft-overlooked area of history. When all was said and done, the Italian political landscape had been radically changed. Thousands of leftists were forced to flee the nation, but ultimately, shocked by the violence, Italian politics moderated.

Did we mention that a Masonic Lodge came very close to overthrowing the government? Strap yourself in. You’re about to take a bumpy ride down an obscure historic lane, where “truth being stranger than fiction” is most certainly true (and well documented).

Background of the Italian Years of Lead

Before diving into the Italian Years of Lead, it’s important to understand the political climate of Italy after the Second World War. The Communist Party was always a strong force in post-war Italian politics. In the first election after the war’s end, in 1946, the Communist Party received 18.9 percent of the vote. Going into the second election at the end of the war, the Communist Party was poised for even greater success, buoyed by their alliance with the Socialist Party – an almost exact replay of what happened in Czechoslovakia. In both cases, the Communist Party had entered into an alliance with naive Socialists, whom they quickly outfoxed, dominating the electoral combination of nominal equals.

Before diving into the Italian Years of Lead, it’s important to understand the political climate of Italy after the Second World War. The Communist Party was always a strong force in post-war Italian politics. In the first election after the war’s end, in 1946, the Communist Party received 18.9 percent of the vote. Going into the second election at the end of the war, the Communist Party was poised for even greater success, buoyed by their alliance with the Socialist Party – an almost exact replay of what happened in Czechoslovakia. In both cases, the Communist Party had entered into an alliance with naive Socialists, whom they quickly outfoxed, dominating the electoral combination of nominal equals.

Meanwhile, in Czechoslovakia, a Communist coup d’etat was engineered by a section of the government dominated by Communist elected officials. The CIA stepped in, putting their thumb on the scale in an attempt to prevent the Communists from succeeding in Italy as well. This was one of the first battles in the burgeoning Cold War. All told, the CIA funneled somewhere between $10 and $20 million to defeat the Communists (between $106 and $212 million in 2019 dollars). In contrast, the Soviets spent between $8 and $10 million every month to ensure a Communist victory in the elections.

In an incredibly tense and vitriolic campaign, the Christian Democrats eventually bested the Communists, getting 48 percent of the vote to the Communist Party’s 31. The anti-Communist Socialist grouping netted the balance of the remainder, with small parties picking up the rest, as is common in Italy. The Christian Democrats formed a broad tent coalition, despite having an electoral mandate that did not require it, bringing in Liberals, Republicans and Social Democrats.

However, this did not end the involvement of the CIA in Italy, nor the strength of the Communist Party. The CIA spent an average of $5 million annually in Italy, both to prop up center-right governments and to weaken the influence of the trade unions, who traditionally supported the Communist Party. From 1948 until the first Italian election after the fall of Communism in 1992, the Communist Party polled between 22 and 33 percent in Italian elections, a fact that always filled the CIA with dread.

It is worth briefly mentioning that the successor to the National / Republican Fascist Party, the Italian Social Movement, never polled higher than 9 percent.

The CIA was also a key player in Italy through Gladio, the stay-behind organization it backed in Italy to fight a guerilla insurgency against a potential Communist takeover of the country. The extent of Gladio’s direct involvement in the Years of Lead is a hotly debated topic among historians.

The Hot Autumn of 1969 and 1970

Throughout the 1960s, Italy became increasingly industrialized and modernized, which led to discontent among both the left and the right. These forces were very briefly united in a series of protests in Italy in 1968. However, the similarities between the far-left and far-right were too tenuous, and the establishment parties were largely skeptical of the counter-cultural orientation of the young radicals.

These protests set the stage for what is known in Italy as the “Hot Autumn.” This was a series of wildcat strikes throughout Italy in its industrial sectors, largely in response to layoffs due to increased efficiencies in industrial production. It was the basis of a growing Communist Party, and one that was shifting even further to the left in response to networks of activists known as “autonomists.”

The Italian Years of Lead were in some part a reaction of the far-right to this ascendant Communist movement. However, as stated above, international intelligence agencies were deeply involved and the truth of how the whole thing started moving is incredibly complex.

The Years of Lead Claim Their First Victim: The Death of Antonio Annarumma

The initial movement in the Years of Lead was simply a continuation of the Hot Autumn. A group of autonomist students and workers occupied a FIAT factory in Milan. During a related protest in November 1969, Milan police officer Antonio Annarumma was killed by an iron tube. The leftists protesters claimed that this was an accident, however, the courts found differently.

The initial movement in the Years of Lead was simply a continuation of the Hot Autumn. A group of autonomist students and workers occupied a FIAT factory in Milan. During a related protest in November 1969, Milan police officer Antonio Annarumma was killed by an iron tube. The leftists protesters claimed that this was an accident, however, the courts found differently.

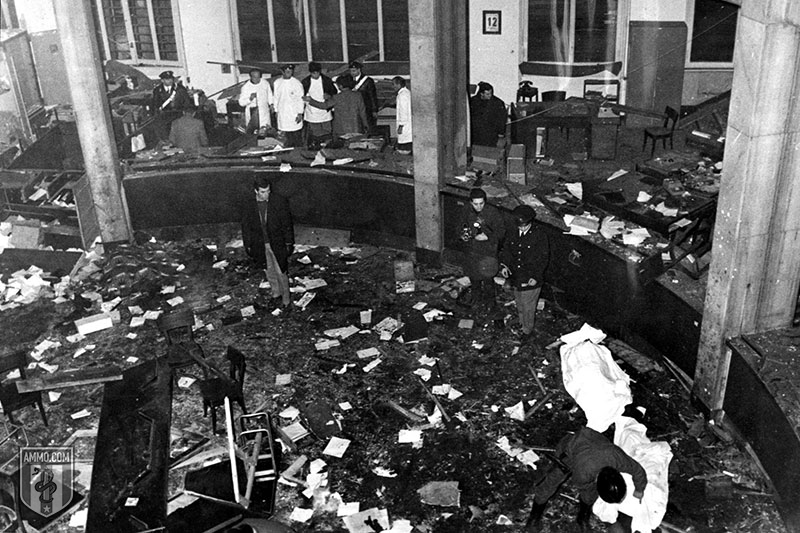

This was followed by the first, but certainly not the last, bombing in the Italian Years of Lead. On December 12, 1969, a bomb went off in the National Agrarian Bank’s headquarters in Piazza Fontana, some 200 meters from the Duomo. The bomb claimed the lives of 17 people, with another 88 wounded.

At first, the press and the police blamed the attack on anarchists. Police arrested prominent anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli, who died under suspicious circumstances when he fell from the fourth-story window of the police building while in custody. The three police in charge were later investigated, but cleared of any wrongdoing. Police commissioner Luigi Calabresi was later assassinated by autonomist paramilitary group Lotta Continua as revenge for the death of Pinelli.

Another anarchist, Pietro Valpreda, was arrested and held without charge for three years after a cab driver identified him as his “suspicious passenger.” He was later exonerated.

Approximately three years after the bombing, the police finally switched their focus from investigating anarchist operatives to looking into the far-right, neo-fascist grouping Ordine Nuovo (New Order). On March 3, 1972, Italian police arrested Franco Freda, Giovanni Ventura and Ordine Nuovo founder Pino Rauti, who consistently described himself as a non-fascist and a leftist throughout his lengthy political career on the far-right in Italy. The first two were eventually convicted for two separate bombings in 1987, and sentenced to 16 years.

The Masonic P2 Lodge – which we will go into in greater detail later – played a key role in running interference for the accused through their member General Gianandelio Maletti, the head of the Servizio Informazioni Difesa, the Italian state security services.

Curiously, the initial reaction of the police was not far off from what Ordine Nuovo had intended. The bombings were meant not just to create a sense of overall terror, but to implicate the Communist movement in Italy.

The Left Strikes Back: The Formation of the Red Brigades

In reaction to Ordine Nuovo and inspired by Latin American guerilla movements, as well as similar movements on the continent, the Brigate Rosse was formed in 1970. As was the case with many far-left groups in Italy and Germany at the time, they saw the post-war government as a mere continuation of the previous fascist regime, now backed by NATO.

They grew out of a series of strikes against the Sit-Siemens corporation. The bulk of their initial leadership were young and had been expelled from the Italian Communist Party’s youth movement for their extremism. Their first action was a simple one: They set ablaze the car of Sit-Siemens corporate leader, Giuseppe Leoni. No one was hurt.

The Red Brigades and Ordine Nuovo each committed a number of actions throughout the Italian Years of Lead, and will pop up a number of times throughout this article. A failed fascist coup would soon increase the tensions in Italy.

The Failed Fascist Coup d’etat: Golpe Borghese

The failed fascist coup of 1970 probably had very little chance of success. Still, it became a watchword on the Italian left. Hundreds of members of Neo-Nazi group National Vanguard plotted to overthrow the government with 187 allies from the Italian Forestry Service, of all places.

The plan was to seize the offices of RAI, the state Italian broadcaster. This is what the Forestry Service members were in charge of. Vanguard militants planned to assassinate the President of Italy, Giuseppe Saragat, as well as Italian police chief Angelo Vicari, while seizing the Quirinale, the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Defense. The Vanguard would then have a large cache of weapons at the ready. High-ranking military officials including Air Force General Giuseppe Casero were involved, as was the Sicilian mafia. The plotters believed they would be supported by NATO forces in the Mediterrenean, however, support for the coup was marginal within the CIA and other intelligence services, which saw the status quo as the best policy in the region.

A couple of people entered the Ministry of the Interior, but the coup otherwise went nowhere, as it was called off at the last minute. All 46 plotters were eventually acquitted, because the coup was such a massive failure.

The Years of Lead Ramp Up: After the Coup

While the coup was somewhat comical in its ineffectiveness, it was like throwing gas on the fire of the Years of Lead. Armored car driver Alessandro Floris was assassinated by the October 22 Group. The arrest of his assassin, Mario Rossi, led to the dismantling of the group by Italian police, who quickly stumbled onto the cache of weapons and propaganda the group was hoarding. This group was considered a precursor of the Red Brigades who, in April 1974, kidnapped a judge in an attempt to free October 22 Group prisoners.

While the coup was somewhat comical in its ineffectiveness, it was like throwing gas on the fire of the Years of Lead. Armored car driver Alessandro Floris was assassinated by the October 22 Group. The arrest of his assassin, Mario Rossi, led to the dismantling of the group by Italian police, who quickly stumbled onto the cache of weapons and propaganda the group was hoarding. This group was considered a precursor of the Red Brigades who, in April 1974, kidnapped a judge in an attempt to free October 22 Group prisoners.

Police officer Luigi Calabresi was the next victim, assassinated on May 17, 1972. Police first suspected Lotta Continua, then shifted their focus to neofascist militants. Three members of Lotta Continua were eventually convicted 16 years after his death.

Next was the May 31, 1972 bombing in Peteano, which claimed the lives of three carabinieri. This was initially blamed on Lotta Continua as well, however, it was later found out to be the work of neofascist terrorist Vincenzo Vinciguerra. Much like the earlier neofascist bombing, this was a false flag, with the intention of making the Italian state act in a more authoritarian manner. The Italian state security services helped Vinciguerra escape Italy to the safe harbor of Francisco Franco’s Spain. Further investigation found that Nuovo Ordo had worked closely with the Italian state security services to help execute the bombing.

On April 16, 1973, two members of Potere Operaio attacked the house of Italian Social Movement member Mario Mattei with a flammable device. He escaped unscathed, while his two sons, aged 8 and 22, burned to death. Their charred bodies were found embracing one another after the fire was over. It is worth noting that the Italian Social Movement, a small, but mainstream party in Italy, played no part in the Italian Years of Lead, whose right-wing actors were cut from a far more radical bent than the Social Movement’s parliamentarians.

One month later, the police headquarters in Milan was bombed by anarchist Gianfranco Bertoli. The attack killed four and wounded 75. In May of 1974, the Piazza della Loggia in Brescia was bombed by Ordine Nuovo. Eight people died and 102 were injured. One month later, two members of the Italian Social Movement were murdered in Padua, murder initially ascribed (like the burning of Mario Mattei’s home) to infighting within the Italian right. The Red Brigades later claimed the murders – their first. Previously, the organization had only participated in bank robberies, kidnappings and bombings. A second fascist coup was planned for July 1974, but never executed. On August 4, 1974, Nuovo Ordine bombed the Italicus Express train, killing 12 and injuring 48. While Nuovo Ordine claimed responsibility, no perpetrators were ever brought to justice.

For those having trouble keeping track, the right-wing terrorist groups mostly bombed things in an attempt to get the government to crack down, while the left-wing terrorist groups specialized in kidnappings and targeted assassinations.

Some Red Brigade leaders were arrested in 1974, but the organization continued – as did the violence. Indeed, the violence began to be somewhat accepted as part of life in Italy at the time. The far-left sympathizers generally claimed that the violence attributed to the far-left was in fact false flag operations on the part of the far-right.

The murders, bombings and kidnappings are too numerous to go into detail starting around 1975. This was the year that left-wing groups killed MSI militant Mikis Mantakas during a riot and MSI militant Sergio Ramelli was beaten to death by members of Avanguardia Operaia (a successor group to Lotta Continua) with wrenches. Left-wing student activist Alberto Brasili was stabbed to death by neo-fascists and carabinieri Giovanni D’Alfonso was murdered by the Red Brigades.

Things only intensified in 1976. Left-wing group Prima Linea assassinated MSI lawyer Enrico Pedenovi. Neo-fascist Pierluigi Concutelli assassinated Judge Vittorio Occorsio. In 1976, there were several more murders, almost all of them perpetrated by left-wing terrorist groups, including the murder of Carlo Casalegno, deputy director of liberal newspaper La Stampa. In 1978, there were no fewer than 12 murders by left-wing groups, most of them by the Red Brigades, including a security chief for FIAT motors, three police officers, three judges, a university professor, and a notary.

Things had reached a fever pitch and it seemed that Italy would never return to a peaceful normal.

Italy Turns a Corner: Kidnapping of Aldo Moro

Italy finally turned a corner when the Red Brigades went a step too far: They kidnapped Italian former Prime Minister Aldo Moro, who at the time was the president of the mainstream center-right party in Italy, the Christian Democrats.

Italy finally turned a corner when the Red Brigades went a step too far: They kidnapped Italian former Prime Minister Aldo Moro, who at the time was the president of the mainstream center-right party in Italy, the Christian Democrats.

The former Prime Minister’s car was ambushed by members of the Red Brigades on March 16, 1978. The assailants fired 91 shots at his five bodyguards, all of whom were killed in the attack. Prima Linea militant Mario Ferrandi said that at the time, he knew that everything was going to change – the Red Brigades had finally bitten off more than they could chew.

The actual motive of the attack is not entirely clear, but it was probably to disrupt negotiations between Christian Democracy and the Communist Party of Italy. The latter was finally being brought into government, albeit in indirect roles, for the first time since the end of the Second World War. Moro wrote 86 letters during the 55 days he was held in captivity, including to figures such as Pope Paul VI, but also to his family. Some were sent and delivered, others were discovered later.

Conclusive evidence demonstrates that Moro was not tortured. He was, however, put on a “trial” by a “people’s court” of Red Brigades, with predictable results. The Red Brigades wanted to trade him for terrorists imprisoned, and eventually requested only one.

Moro’s body was found on the day of his murder, May 9, 1978. The P2 Lodge has been implicated in Moro’s kidnapping.

The response of the Italian government – and indeed, the Italian public – to the kidnapping and murder of a former Prime Minister was sweeping and had consequences far beyond a simple winding down of the Italian Years of Lead.

First and foremost, the Historic Compromise brokered between the Christian Democracy and the Italian Communist Party was over. It had been unpopular with Italy’s European allies. But the kidnapping of a man considered the natural next president of the republic killed it stone dead. The intention was for Italy’s two major parties to rule in a grand coalition. The Historic Compromise officially ended in November 1980.

The president, Giovanni Leone, resigned less than a month after the kidnapping. The government’s response was largely seen as a failure. The Communist Party declined in influence, while the Christian Democracy remained steady until the early 90s, when it began to be supplanted by the more popular Lega Nord, now known simply as the Lega.

It is worth noting that, much as the MSI was at odds with the far-right terrorist groups, so too were the far-left terrorist groups largely opposed by the Communist Party and outright despised by trade unionists.

Oddly, despite a massive government clampdown, 1979 was the bloodiest year of the Years of Lead, with 659 attacks, including 11 assassinations. Among the victims that year were four policemen, a Lieutenant Colonel of the carabinieri, a trade unionist, a bartender and investigative journalist, a judge, and a university student. All of these were committed by leftist terrorist groups. Additionally, the Red Brigades shot five teachers and five students in the legs that year.

1980 topped 1979 in terms of assassinations with a total of 17. The victims that year included five policemen, a carabinieri general, a petrochemical manager, a cook, four judges, a security guard, and a journalist. Prima Linea even turned on one of its own that year, killing William Vaccher on suspicion of treason to the group. All but one of these were committed by left-wing groups.

The Biggest Attack: The Bologna Massacre

While the Italian left had been pushing big numbers with assassination, a new group on the far-right, the Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari, formed by dissident members of the Italian Social Movement explicitly with the purpose of committing counter-attacks against the left, was planning something big – the Bologna Massacre. This bombing of the Bologna Centrale train station killed 85 and wounded more than 200. While the group denied involvement, several of its members were sentenced for the bombing.

While the Italian left had been pushing big numbers with assassination, a new group on the far-right, the Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari, formed by dissident members of the Italian Social Movement explicitly with the purpose of committing counter-attacks against the left, was planning something big – the Bologna Massacre. This bombing of the Bologna Centrale train station killed 85 and wounded more than 200. While the group denied involvement, several of its members were sentenced for the bombing.

Christian Democratic Prime Minister Francesco Cossiga’s statement on the attack cuts to the heart of the difference between the left- and right-wing actions during the Years of Lead:

“Unlike leftist terrorism, which strikes at the heart of the state through its representatives, right-wing terrorism prefers acts such as massacres because acts of extreme violence promote panic and impulsive reactions.”

In short, the strategy of the left was more akin to a Third World guerilla insurrection, while the right hoped to provoke the state into clamping down on the left through false flags and other large-scale acts of terrorism.

Two members of the NAR were convicted, Francesca Mambro and Giuseppe Valerio “Giusva” Fioravanti, the latter a former Italian child actor. The pair later married and had a daughter. Both admit to having committed terrorist acts, but maintain their innocence with regard to the Bologna Massacre.

The Years of Lead Wind Down

Left-wing violence in Italy related to the Years of Lead continued as far as 1988. However, after the Bologna Massacre, things had died down considerably. 1981 saw three kidnappings resulting in two murders. The third, the kidnapping of American General James L. Dozier, then deputy-chief of NATO’s Southern European forces, was freed by an anti-terrorist squad.

In 1982, the Red Brigades attacked a military convoy, killing a corporal and two police officers. The assailants were never apprehended. Later that year, two guards were killed by Red Brigades during a bank robbery.

1983 was completely quiet, and thus might be a good place to mark the end of the Years of Lead proper. However, in 1984, American diplomat and Director General of international peacekeeping force, Multinational Force and Observers, Leamon Hunt, was killed by the Red Brigades. In 1985, the Red Brigades killed an economist and a policeman. In 1986, they assassinated the Mayor of Florence. Italian Air Force General Licio Giorgieri was assassinated by the Brigades in 1987. In 1988, the Red Brigades committed their final assassination, that of Senator Roberto Ruffilli.

On October 23rd of that year, the Red Brigades declared that their war against the state was over.

In 1985, French President Francois Mitterand declared that he would not extradite convicted terrorists back to Italy. Instead, he aimed to integrate them into French society. Brazil and Nicaragua have likewise provided safe haven for left-wing terrorists of the Italian Years of Lead, most notably Alessio Casimirri, one of Moro’s kidnappers who owns a restaurant in Nicaragua.

Epilogue: The P2 Affair and the Strategy of Tension

While the players were mostly firmly identifiable either as being on the left or on the right, one group played both sides: The shadowy Masonic Lodge in exile Propaganda Due, also known as the P2 Lodge.

While the players were mostly firmly identifiable either as being on the left or on the right, one group played both sides: The shadowy Masonic Lodge in exile Propaganda Due, also known as the P2 Lodge.

While the very mention of Freemasonry generally has people reaching for their tin foil hats, the P2 Lodge’s involvement in the Years of Lead – and other clandestine machinations within the Italian State – are very well documented, primarily through obstruction and obfuscation of the resulting investigations.

The P2 Lodge and the extent of its influence was discovered in March 1981, when police found a list of 962 alleged members, including future Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and pretender to the Italian throne Victor Emmanuel. The ensuing scandal forced the resignation of the Italian government at the time.

In July 1982, the ultimate aims of the Lodge were discovered, two documents entitled “Memorandum sulla situazione italiana” and “Piano di rinascita democratica.” These documents identified the Italian Communist Party and the trade unions as the biggest threats, proposing a grand alliance between the Christian Democrats and the Communists as the way forward. It also outlined a means to control the media and political parties through extensive bribery.

A government report commissioned by the successors of the Communist Party, the Left Democrats, as well as Swiss historian Daniele Ganser have claimed that the Years of Lead were in large part the result of a “strategy of tension” by NATO, the CIA, Gladio and their allies (including the P2 Lodge). This is where actors, generally in the government, create or allow a state of hostility for the purpose of making political capital out of it.

It is entirely possible that the Years of Lead occurred due to a purposeful lack of action on the part of the Italian government, which saw the chaos as an opportunity for greater power.

The American Years of Lead?

America is a long way from its own Years of Lead. What’s more, one of the principal ingredients – material support from powerful foreign governments – seems to be lacking. However, as the American political landscape becomes both increasingly radicalized and polarized, with extremist groups on the left and right growing in numbers, militancy and desperation, it’s not too hard to imagine that they might start shooting at one another in the very near future.

That won’t kick off a civil war, but it will make life in America considerably more tense and unpleasant.

Article source: Ammo.com

Sam Jacobs is the lead writer and chief historian with Ammo.com, and is the driving intellectual force behind the content in the Resistance Library. He is proud to see his work name-checked in places like Bloomberg, USA Today and National Review, but he is far more proud to see his work republished on websites like ZeroHedge, Lew Rockwell and Sons of Liberty Media.

How many firearms does Sam own and what’s his everyday carry? That’s between him and the NSA.

Subscribe to Activist Post for truth, peace, and freedom news. Become an Activist Post Patron for as little as $1 per month at Patreon. Follow us on SoMee, Flote, Minds, Twitter, and Steemit.

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.

Be the first to comment on "The Italian Years of Lead: Could the Secret “Strategy of Tension” Foreshadow America’s Future?"