The Do-It-Yourself Decade

A great many people laud traditional values and lifestyles, but they leave out the hard part: it take a heck of a lot of work, effort and sacrifice.

I’m calling the next ten years The Do-It-Yourself Decade, as whatever we want to happen will increasingly be up to us to do for ourselves. After decades of fostering passive consumption–let someone else make or do the stuff we want / need–we’re entering an era that will no longer be optimized for passive consumption, it will be optimized for active participation and production.

That this will be jarring reflects just how dependent we’ve become on long global supply chains, corporations and the state for the essentials of life, which include not just stuff but a system of values, contexts and incentives that go with the stuff.

For obvious reasons, many people think we’ve changed captains before the Titanic has been mortally wounded by the collision with the iceberg. This is a comforting thought, because it’s based on the idea that those at the top of the Power Pyramid will save us without us having to get our hands dirty.

Alas, we’re changing captains after the Titanic has already struck the iceberg and its sinking is already fated. As I outlined in a previous post, Extremes Become More Extreme, and then the system’s inherent fragilities and vulnerabilities play out, much to everyone’s surprise. Things no longer work as expected, stuff is no longer available as expected, and stuff doesn’t get fixed as expected.

This is what happens to systems that have been hollowed out and duct-taped with play-acting “solutions,” in which play-acting a solution is delusionally presumed to actually fix what’s broken when the whole point of the play-acting is to mask the depth of the actual problems and paper it all over with a narrative, as if the problem was one of perception rather than one of the real world.

In the decade ahead, if we want solutions / fixes /changes, we’re going to have to make them happen in our own lives. We can start with the full range of meaning in the phrase get lean: replace the fat of wasted time, “entertainment,” “news,” consumerist indulgences and relying on the government and corporations to take care of us with the often difficult and tedious work of becoming less dependent on institutions and companies to secure what we value.

If we want a secure supply of food, grow some of our own. If we want to be healthy, then get healthy on our own. If we want a career, then hammer one out ourselves by owning our skills and taking responsibility for getting full value for them. If we want an education, then get it ourselves, not by borrowing a fortune but by figuring out how to learn what we want to learn on our own, at the lowest possible cost in time and money.

If we want a secure water supply, then we better buy a water tank. If we want reliable electricity, then we better arrange to save up and invest in our own system, however modest. If it charges phones, keeps the Internet connected, powers a few lights, and is sustainable, then that’s a lot better than having nothing but a flashlight.

Get lean means getting rid of the garbage weighing us down: the garbage food, the garbage consumption of junk we don’t need, the garbage social media and “entertainment,” the garbage debt, the junk we don’t even use that’s in storage, the garbage unpaid shadow work imposed by our corporate masters and government agencies, and the garbage narratives that keep us focused on what the globalists might be doing instead of what we can do for ourselves in the real world.

Roughly 80% of the populace has been packed into mega-cities and urban sprawl. This environment of complete dependence on complex systems operated by the state or corporations is optimized for a mindset of dependence–“somebody do something!”– and for passive consumption: earn money performing some task in the Machine and then spend it buying stuff and services.

It’s a massive change to re-think this dependency and sobering lack of self-reliance, for to remedy those deficiencies may require moving all the big pieces of our lives, more or less all at once. It’s daunting.

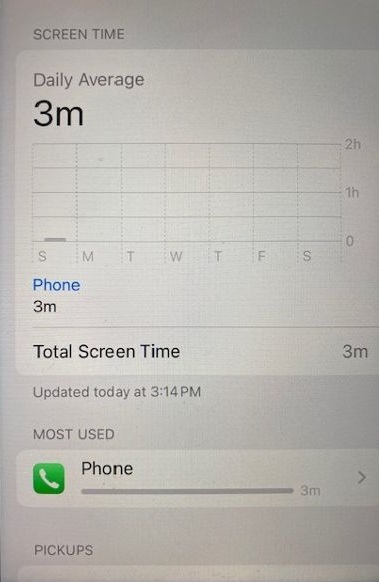

The Do-It-Yourself Decade means no more spending six hours a day staring at a screen for amusement / distraction, for there’s too much real work to do. Here’s what your phone’s screen time should look like, once the transition from consumption and dependence to production and self-reliance has occurred.

A great many people laud traditional values and lifestyles, but they leave out the hard part: it take a heck of a lot of work, effort and sacrifice. Teaching kids by letting them do real stuff in the real world takes time and effort. Making a meal for an elderly person and getting them to the table takes time and effort, especially when you’re already stretched thin. Learning difficult things on our own takes time and effort. All the good things in life demand tremendous sacrifices, and I don’t mean things relating to making, spending or saving money. In a society optimized for finance, ease and convenience, these realities don’t play to the dominant narratives.

The real world demands far more of us than finance and the online / passive consumption world. Shopping is not a replacement for skill, effort and taking responsibility for things that have been offloaded onto others.

The problem is systems tend to break down in a non-linear fashion, as the decay is not visible. This means predictability is low and things tend to happen all at once. Alternatively, things stop working a bit at a time, and the frogs are slowly boiled before they realize the situation demands some sort of extraordinary action.

These are hard things to consider. They are not comforting in the sense of reassuring us finance, ease and convenience are permanent thanks to technology and AI. But if we consider the meaning of freedom and liberty not as cliches, but as freedom from dependence and freedom of movement, then considering hard things becomes assuring in a much different way.

The band is still playing and the ship feels unsinkable. That’s an easy narrative to find comfort in. But is it realistic? Time will tell.

And yes, that’s my phone and my Skilsaw.