Five years ago, in March 2020, Yale sociologist and physician Nicholas Christakis MD, PhD, MPH took to Twitter to marvel at China’s response to SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind Covid-19. In a detailed thread, he described China’s “social nuclear weapon” (of the people-clearing ‘neutron bomb’ -variety?): unprecedented lockdowns, movement restrictions on 930 million people, and a collectivist culture harnessed by an authoritarian regime. He framed it as a Newtonian feat: the sheer force required to stop the virus revealed its power. Contrast this with Stanford’s Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, MD, PhD, MA (economics): equally credentialed, but clear-eyed (the French term is “clairvoyant”), who early on delineated Covi’s stratified risk and urged an adaptive model over authoritarian mimicry.

For Christakis, China’s drop in cases from hundreds daily to a mere 46 in a nation of 1.4 billion was “astonishing.” But beneath the awe, a question lingers for us today: What was the real “virus” China was fighting—and why didn’t we, in the supposedly free West, push back harder on the narrative?

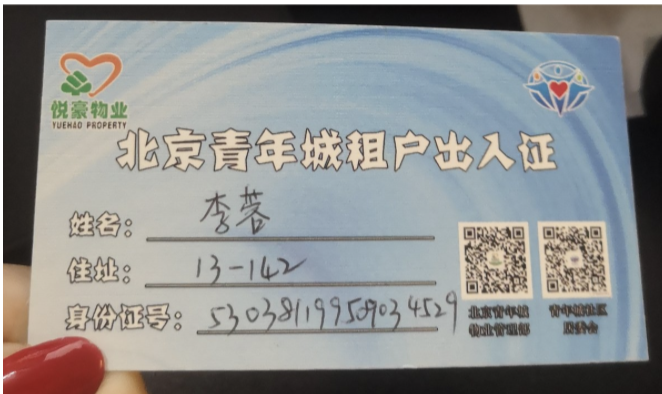

Christakis’ thread, preserved in its 35-tweet glory, reads like a love letter to China’s public health machinery. He details “closed-off management” (which China later disavowed)—permits for one person per household to leave,

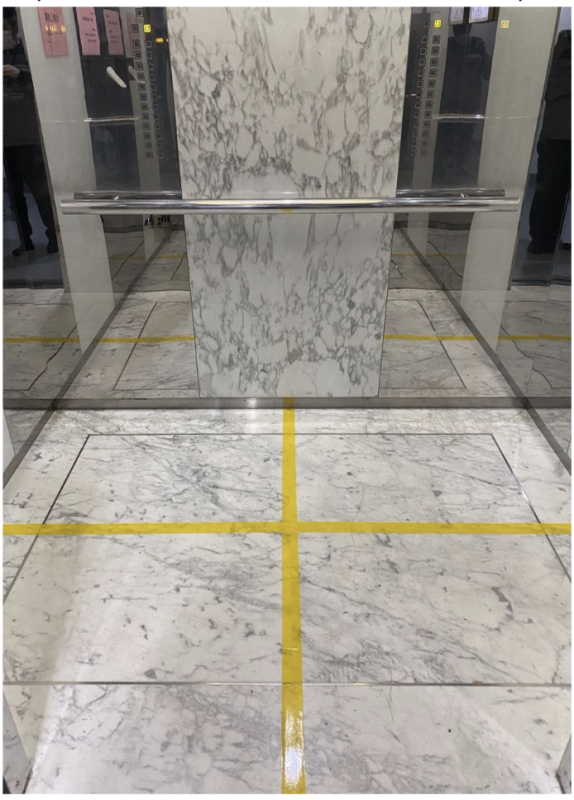

temperature checks, and disinfected elevators with taped-off occupancy limits.

He chuckles at gallows humor about kids’ taking online PE classes while parents plead for quiet. He cites a study showing the virus’s reproductive rate (Re) plummeting from 3.8 to 0.32, proof that the epidemic was being snuffed out. China’s success (sic) leaned on “China’s government being authoritarian…but COVID-19 control was dramatic,” Christakis sighs, wistfully.

Yet, he never questions the cost or the context (or the underlying validity, purpose, and reproducibility of data from an authoritarian regime – at the very least, at “cold” war with us; or with Trump ’45). He nods to Dr. Li Wenliang’s death—a whistleblower silenced by the state—but moves on, as if it’s a footnote in a grand triumph.

Let’s rewind to 2003, to “Classic Coke”—the original SARS outbreak. China faced a similar respiratory virus, and its response foreshadowed 2020. Back then, no vaccine emerged despite frantic efforts. Why? Respiratory viruses like SARS and its sequel, SARS-CoV-2, mutate fast and pose risks like antibody-dependent enhancement, where vaccines might worsen illness in some cases.

China’s 2003 playbook wasn’t just about health—it was about control. Protests erupted, notably in cities like Chagugang (April 29, 2003), when infected patients were shuttled between regions, sparking riots over perceived negligence. Tiananmen Square’s shadow loomed large; political unrest was the real contagion Beijing feared. Susan Shirk in China: Fragile Superpower (2007) noted that (original) SARS exposed governance weaknesses, amplifying public discontent. Fast forward to 2020, and Xi Jinping’s “severe, prophylactic clamp” looks less like a health strategy and more like a preemptive strike against social upheaval.

Between 2003 and 2020—an interregnum worth dissecting—China chased a potential SARS vaccine. Labs used ferrets as vaccine subjects. One can ferret out that they did not fare well.

The Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), established in 1956 but revamped post-SARS with French collaboration, became a hub for coronavirus research, partly driven by 2003’s lessons.

Billions were poured in, yet by the mid-2010s, efforts stalled. Why? Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), where vaccines trigger worse disease outcomes, loomed as a brick wall. SARS-CoV’s mutability didn’t help. Dr. Anthony Fauci himself later mused that respiratory viruses resist systemic vaccines.

“Attempting to control mucosal respiratory viruses with systemically administered non-replicating vaccines has thus far been largely unsuccessful…The importance of mucosal secretory IgA (sIgA) in pathogen-specific responses against respiratory viral infections has long been appreciated for influenza viruses.”

Despite this hard-earned skepticism and knowledge, by 2020, China projected an image of triumph through control, sidelining the caution such science demanded.

Now, consider the Diamond Princess cruise ship—a floating lab that docked in our laps in February 2020. By March 9, when Christakis tweeted, data was clear: 3,711 passengers and crew, a confined petri dish, yielded 712 infections. Yet, among the young and healthy, symptoms were often absent. Illness skewed heavily toward the elderly, and by that date, zero deaths had been recorded (seven later occurred, all older patients). This serendipity of effectively a “$1 trillion experiment” (if priorly designed) screamed a truth: Covid-19 wasn’t an equal-opportunity killer. Fauci knew this. Why didn’t he shout it from the rooftops? Why didn’t Christakis mention it? Instead, the narrative fixated on China’s draconian model, as if we had no choice but to follow.

And follow we did. Stateside, we adopted lockdowns, school closures, and social distancing—echoes of China’s “closed-off management”—despite our supposed allergy to authoritarianism. Christakis laments that the US lacks China’s tools, but he doesn’t dwell on whether we should’ve wanted them. He doesn’t ask what China’s real “virus” was. Was it SARS-CoV-2, or the specter of unrest at home? Or, as some speculate, a geopolitical jab—anti-Trump agitprop to destabilize his economy and ascendancy amid trade wars and tariffs? Our own “useful idiots,” as Lenin might’ve called them, lapped it up, amplifying China’s narrative without a skeptical squint. Why?

The SARS 2003 parallel offers a clue. Post-outbreak, China faced no global applause for its heavy hand—just criticism and internal grumbling. In 2020, China doubled down, projecting competence to the world while quashing dissent. Li Wenliang’s death wasn’t just a tragedy; it was a warning. Thousands still mourn him daily on Weibo, a quiet rebellion against the state’s grip. Christakis notes this but doesn’t connect the dots: China’s “astonishing” control came at a human cost we in the West ignored, then mimicked.

So, why the blind spot? Groupthink, perhaps. Christakis, like many in 2020’s expert class, rode the wave of panic, dazzled by China’s numbers without questioning the why or the what-next. The Diamond Princess begged us to stratify risk—protect the old, let the young live—but we didn’t. SARS 2003 begged us to doubt vaccine dreams and fear political overreach, but we didn’t. Instead, we bought the story that only a “social nuclear weapon” could save us, never asking if the cure was worse than the disease.

Five years later, the “cool kids” (like you: smart, curious, skeptical) can see through the haze. China’s response wasn’t just about a virus; it was about power. The US didn’t lack tools; its public health leaders lacked the nerve to chart a different course (or were complicit or compromised). The real lesson? Question the narrative. Dig into the data. And when someone hands you a “Classic Coke” story, check the ingredients.

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.